Stanley L. Wood

Stanley Llewellyn Wood | |

|---|---|

| Born | 10 December 1866 Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Died | 1 March 1928 (aged 61) Palmers Green, Enfield, London, England |

| Nationality | Welsh |

| Other names | Stanley L. Wood |

| Occupation(s) | Illustrator and artist |

| Years active | – |

| Known for | Dramatic drawings of horses in motion |

| Notable work | Captain Kettle |

Stanley Llewellyn Wood (10 December 1866 – 1 March 1928) was a prolific Welsh illustrator who travelled widely. He was known for his portrayals of horses in action and also for his black-and-white illustrations for the Captain Kettle stories by C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne.

Early life

[edit]

Wood's Birth Certificate shows that he was born in Christchurch, Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, on 10 December 1866.[note 1] His parents were Stanley James Wood (c. 1839 – 27 May 1877), a cement manufacturer and entrepreneur, and Charlotte Atkins (c. 1839 – ). Wood's father was declared bankrupt in 1861,[1] and was before the bankruptcy court again in 1869.[2][3] Wood was the last of five children, and the only boy.

In 1873, George Grant,[note 2] a Scottish silk merchant in London bought some 77 square miles of land in Kansas and proposed to set up an English colony there which he called Victoria.[7] Wood's father sunk his money into the scheme and the family travelled to Kansas in 1873, when Wood was five or six years old. Grant had made him commissioner of streets in Victoria as an inducement.[6]

When the family arrived in Victoria they found, not the bustling colony they had been promised, but a single two-storey stone building, the railway station, which also functioned as a hotel. Many of the other colonists were young men who were on allowance from their families, and were more intent on enjoying themselves than farming. The family found the carousing of the young men, and of the local cowboys, was intolerable and fled to Kansas City, with the very last of their money. Wood's father got a job with the Union Pacific land department at Lawrence, Kansas, and the family moved and the children attended school there.[6]

However, their hardships were not over. Still seeking his fortune, Woods' father left his job in Lawrence and began to travel around Kansas demonstrating a patent well-digging auger. He was demonstrating the auger at a farm near Wichita, Kansas, on 27 May 1877, when he experience some symptoms that made him rush to the doctor's office. He died in the doctor's office at 4pm, just as they began to try and treat him.[8] The family's troubles were not over though. They were living in a ranch-house outside the town where the former occupants were buried in the garden after being killed in an Indian raid. The new widow was horrified to find one night that a party of Indians had surrounded the house and she had the children put on boots and clump around and bang doors so that those outside would thing there was a part of cowboys in the house.[9] The family immediately returned to England, although Wood visited Lawrence several times in later life, and his mother visited at least once.[6]

The 1881 census found the family at 4 Mornington street, apart from the eldest Amy Phoebe (Oct 1860- – 1902).[note 3] Wood's second eldest sister Jessie M. was an artist's apprentice at the time. She later travelled to New York to work for the Redfern fashion house as a designer. Eventually she became the drama critic of the New York Journal at a salary of $250 a week, and illustrated her reviews with her own illustrations.[6]

Work

[edit]The 1891 census found Wood at the same address, but this time all of his sisters had left. He now recorded his profession as artist, but it is not clear what formal training he had had. He was an accomplished artist, having work accepted by the Royal Academy up to 1905, as follows:[10]

- 1892. 361 Royal Horse Artillery going into action, Afghan Campaign.

- 1894. 391 A battle incident, horse artillery going in under fire.

- 1895. 107 Halting the battery, Horse Artillery coming into position.

- 1897. 1009 A surrender under protest, an incident in the Matabele war.

- 1903. 574 A bucking broncho, souvenir of Texas.

Wood exhibited at least two other works at the Academy as Greenwall states that Wood had seven works exhibited at the Royal Academy of which five had a military theme.[note 4][11] Presumably two of these, one military and on non-military were shown after 1905.[12]: 235

Kirkpatrick states that Wood's first illustration work was The Tales of The Spanish Boccaccio: Count Lucanor: Or the Fifty Pleasant Stories of Patronio translated by James York from the original by Prince Don Juan Manuel published in 1888 by Pickering & Chatto.[13] The illustration of this book, as on some others he did, was attributed to S. L. Wood, rather than Stanley L. Wood.[14] His next book was The Arabian Nights Entertainments "Aldine" Edition, from the text Of Dr. Jonathan Scott. This consisted of four large 600 page volumes. It was also published by Pickering & Chatto and cost 24 shillings (one pound and four shillings). The Times said that "With one or two possible exceptions, the illustrations are fair in themselves and unimpeachable in treatment".[15][note 5]

Wood's first two books were for Pickering & Chatto which Andrew Chatto (1841–1913) owned, but Chatto moved the publishing work to Chatto & Windus. Houfe notes that Wood was "employed almost continuously by Messrs Chatto's as an illustrator of boys' adventure stories".[16] The Illustrated London News sent Wood to South Dakota in 1888 where he was able to build on his juvenile experience of the American Old West way of life and for many years produced work with a cowboy and Indian flavour. Harper's published a number of his illustrations, and his Sketches from an Indian Reservation[12]: 235 appeared in the Illustrated London News of 19 January 1889.[17]

In 1890 he produced sixty pen and ink illustrations for Bret Harte A Waif of the Plains.[18] [19]: 537 His illustrations often appeared in early issues of Pearson's Magazine and covered a wide range of genres; notably, he illustrated George Griffith's Stories of Other Worlds (January–July 1900), early science fiction.

His many Africana illustrations included those for the books of Bertram Mitford (1855–1914) - The Gun Runner (1893), The Luck of Gerald Ridgeley (1894), The Curse of Clement Wayneflete (1894), Renshaw Fanning's Quest (1894), The King's Assegai (1894), A Veldt Official (1895) and The Expiation of Wynne Palisser (1896).[12]: 235

In 1900, he did 100 illustrations for an American edition of Richard Burton's The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. Presumably he was awarded this work because of his earlier work on Crellin's Romances of the Old Seraglio.[20]

His illustrations of the Anglo-Boer War appeared in Black & White and Black & White Budget. Most of these featured equestrian scenes.[12]: 58 Some of these illustrations also appeared in L'Illustré Soleil du Dimanche[12]: 67 and one appeared as a cover illustration for War Pictures.[12]: 37 He worked for War Illustrated during World War I.

Examples of book illustration

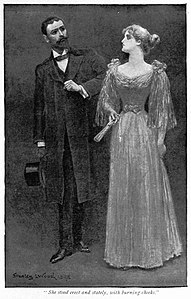

[edit]Marie Connor and her husband Robert Leighton wrote Convict 99. A true story of penal servitude in 1898. Sutherland describes this as: "a powerful anti-prison tract which became their best-known work".[21] The story was published first as a serial in Answers one of the publications produced by Alfred Harmsworth (1865–1922),[note 6] for whom both Connor and Leighton worked. Kemp et al. say that Convict 99 was Connor's greatest success.[22] Wood drew eight illustration of the publication. Those shown below are from the on-line copy at The British Library.[23]

-

Page 076

-

Page 123

-

Page 124

-

Page 152

-

Page 214

-

Page 232

-

Page 252

-

Page 278

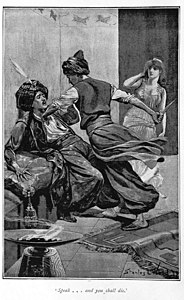

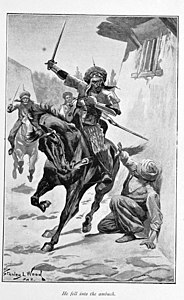

Wood provided 28 illustrations for Romances of the Old Seraglio (1894, Chatto and Windus, London) [20] by H. N. Crellin.[note 7] Romances was a follow-up to Crellin's first book Tales of the Caliph (1887, T Fisher Unwin, London)[27] published under the pseudonym Al Arawiyah, and being nine additional stories set in the world of the Arabian Nights. The book must have been a success as Chatto and Windus issued a new edition of Tales of the Caliph in 1895.[28] Illustrations by courtesy of the British Library.

-

No.1

-

No.2

-

No.3

-

No.4

-

No.5

-

No.6

-

No.7

-

No.8

-

No.9

Family and later life

[edit]Wood married Mary Elizabeth Jenkins (c. 1876 – 1950), the daughter of tailor George Simpson Jenkins at St Dionis Church, Parsons Green, Fulham, London on 21 February 1899. Wood died at his home at 23 Windsor Road, Palmers Green, North London, on 1 March 1928,[29] having been ill for some time.[30] His estate was valued at £114 15s, a pitiable small amount after so many years of work.[29] He was survived by his wife and three adult sons.[30]

Assessment

[edit]Samuels report that there were no auction records for Wood when their encyclopedia was written, but that the estimated price for a 10x14 inch (25.4x35.6 cm) oil-on-board painting showing cowboys spooking a town was about US$1,200 to 1,500 in 1976.[19]: 536-7 Invaluable give more recent estimates, with a 9.9x5 inch (25.1x12.7 cm) pencil drawing estimated at US$2,500 to 4,000 in 2017, and a 24.4x16.5 inch (61.9x41.9 c) oil-on-board painting of a Pony Express estimated at US$2,000 to 3,000 in 2014.[31]

Peppin and Micklethwait say of Wood that: "Most of Wood's illustrations are wash drawings; his emphatic tonal contrasts reproduced well in the halftone process and he was noted for his vigorous, dramatic style and for the authenticity of his American 'frontier' backgrounds."[32] Newbolt refers to Wood's illustrations for the works of G. A. Henty being "in his characteristic vigorous style". Thorpe says that Wood "anticipated the 'headlong dash' and wild west thrillers of the modern films".[33][note 8] Turner characterises him as one of two famous artists associated with the Boy's Own Paper.[34] Cooper notes that Wood is especially noted for his fine action-packed drawings, which certainly helped to bring the printed page alive for boys and girls of the time.[35]

The book-dealer and founding member of the Potomac Corral, Jefferson Chenoweth Dykes better known as Jeff Dykes (-1989), wrote in Fifty Great Western Illustrators - "No better horse artist ever lived than Stanley L. Wood - there was more action in a Stanley Wood illustration than in the story itself".[36]

Notes

[edit]- ^ For whatever reason, his parents did not register his birth until 25 May 1867, when his mother registered his birth at the Caerleon registry. This delay sometimes leads to confusion about his date of birth.

- ^ He is sometimes referred to as Sir George Grant in US newspaper coverage, but he is very much Mr. George Grant in British newspapers. It is not clear if he awarded himself the title, as one 1900 newspaper article seems to imply.[4][5][6]

- ^ An Amy Wood, of the right age and birthplace, was a live-in barmaid at the Duke of York pub at 57 York Road in Lambeth in south London at the time of the census.

- ^ Wood exhibited as follows: one work at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, one work at the Manchester City Art Gallery, seven works at the Royal Academy, and five works at the Royal Institute of Oil Painters.

- ^ Kirkpatrick gives Wood's second book as being by George Fyler Townsend. The Jisc catalogue shows that the version by Fyler, which was published in by Frederick Warne & Co. was illustrated by George Henry Boughton.

- ^ Later better known as Lord Northcliffe.

- ^ Horatio Nelson Crellin (26 March 1841 – 10 December 1912) [24][25], was the son of a surgeon who was born in February 1799 when Horatio Nelson was already extremely popular, hence the name. Crellin himself was a stockbroker, and was, like his father, a member of the Worshipful Company of Pewterers, one of the Livery Companies of the City of London. He was elected Master of the company in 1890.[26]

- ^ Thorpe was writing in 1935, so when he says modern films he means the films of the early 30s.

References

[edit]- ^ "The London Gazette: Bankrupts: Friday, March 1". Reading Mercury (Saturday 02 March 1861): 5. 2 March 1861.

- ^ "Notice of Deed". The London Gazette (23528): 4720. 20 August 1869. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Notice of Entry in Register of Court of bankruptcy". The London Gazette (23528): 4725. 20 August 1869. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "The K. P. Land Grant". The Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas) (Wednesday 26 March 1873): 2. 26 March 1873.

- ^ "The Late Mr. George Grant, of Victoria, Kansas". North British Agriculturist (Wednesday 22 May 1878): 15. 22 May 1878.

- ^ a b c d e "Mrs. Wood's Offer to a Lawrence Girl". Lawrence Daily Journal (Lawrence, Kansas) (Saturday 15 September 1900): 2. 15 September 1900.

- ^ "London Gossip". The Freeman's Journal (Dublin, Ireland) (Monday 01 July 1878): 7. 1 July 1878.

- ^ "A sudden death". The Wichita Weekly Beacon (Wichita, Kansas) (Wednesday 30 May 1877): 5. 30 May 1877.

- ^ "Mr. Stanley L. Wood". The Guardian (London, England) (Monday 05 March 1928): 5. 5 March 1928.

- ^ Graves, Algernon (1905). "Hardy, Paul: Painter". The Royal Academy of Arts: A completed Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol. III: Eadie to Harraden. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 389.

- ^ Johnson, J.; Greutzner, A. (8 June 1905). The Dictionary of British Artists 1880-1940. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 557.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenwall, Ryno (1992). Artists and Illustrators of the Anglo-Boer War. Vlaeberg, Western Cape, South Africa: Fernwood Press. ISBN 0-9583154-2-6.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Robert J. (11 July 1905). "Walter Paget". The Men Who Drew For Boys (And Girls): 101 Forgotten Illustrators of Children's Books: 1844-1970. London: Robert J. Kirkpatrick. pp. 318–324.

- ^ "The Tales of The Spanish Boccaccio: Count Lucanor; Or the Fifty Pleasant Stories of Patronio". Abe Books. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Books of the Week". The Times (Thursday 11 December 1890): 13. 11 December 1890.

- ^ Houfe, Simon (1978). "Fin de Siecle Magazines". Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 183. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Weedy, John. "The Illustrated London News 1889: Jan 19th. Sketches from an Indian Reservation". Illustrated London News. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Harte, Bret; Wood, Stanley L. (1890). A Waif of the Plains. London: Chatto & Windus. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Samuels, Peggy; Samuels, Harold (1985). Samuels' Encyclopedia of Artist of The American West. Castle. ISBN 978-1-55521-014-4.

- ^ a b Crelin, Horatio Nelson (1894). Romances of the Old Seraglio. London: Chatto and Windus. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via The British Library.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1989). "Leighton, Marie". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 369–70.

- ^ Kemp, Sandra; Mitchell, Charlotte; Trotter, David (1997). "Leighton, Mrs Robert". Edwardian Fiction: An Oxford Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 238.

- ^ Conner, Marie; Leighton, Robert (1898). Convict 99. A true story of penal servitude. London: Grant Richards. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/1967-1975: Horatio Nelson Crellin". London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1930. 26 May 1862.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858 and 1996: Surname Crellin and the year of death 1913". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Welch, Charles (1902). "Appendix II: List of Master and Wardens". History of the Worshipful Company of Pewterers of the City of London, based upon their own records. Vol. II. p. 217. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Crelin (as Al Arawiyah), Horatio Nelson (1887). Tales of the Caliph. London: T Fisher Unwin. hdl:2027/uc1.$b252293. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via The Hathi Trust (access may be limited outside the United States).

- ^ Crelin, Horatio Nelson (1895). Tales of the Caliph (New ed.). London: Chatto and Windus. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via The British Library.

- ^ a b "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Wood and the year of death 1928". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Mr. Stanley Wood". The Times (Monday 05 March 1928): 9. 5 March 1928. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Stanley L Wood Auction Price Results". invaluable: The World's premier auctions and galleries. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Peppin, Bridget; Micklethwait, Lucy (1984). "Stanley L. Wood (1866-1928)". Book Illustrators of the Twentieth Century. New York: Arco Publishing Inc. p. 282.

- ^ Thorpe, James (1935). "Some Monthly Magazines". English Illustration: The Nineties. Vol. 139. London: Faber and Faber.

- ^ Turner, E. S (2012). Boys will be Boys: The Story of Sweeney Todd, Deadwood Dick, Sexton Blake, Billy Bunter, Dick Barton et al. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571287888. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cooper, John; Cooper, Jonathan (1998). Children's Fiction 1900-1950. London: Routledge. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 31 July 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Mr. Case Comes to Washington" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2010.